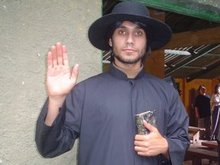

Conner Flaherty

Your host

5/04/2009

2/01/2007

MAKING LEFT FOR DEAD

I have kept a sketchy account of my observations during the shooting of my part of the film. While the scheduled time for shooting the entirety of "Left for Dead" was a break-neck 11 days, I was required to be present for five of those. When I wasn't required to be on the set, I wandered around and tried to soak up as much as possible about how movies are made. What follows are excerpts from my journal. I've included a few photos as well.

DAY ONE OF SHOOTING - WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 17, 2007

The first day for the shoot of the movie “Left for Dead” started with a red school bus that picked up the cast and crew at Plaza San Martin, here in Buenos Aires. It was the first time I had seen so many Argentines so punctual. The director of the movie, Albert Pyun (“The Sword and the Sorceress”, “Cyborg”, “Nemesis”, “Captain America”, “Mean Guns” and some 35 other films) was already waiting for us at our destination: Campanopolis. The production assistant told us to stick together when we get there because “it is very large and very beautiful.”

Campanopolis is such an obscure place that almost no Argentine has ever even heard of it. Yet there it is, 60 kilometers from one of the world’s largest capitals, built in an eerie gothic style with countless windows, balconies, spiral stairways, clock towers, wooden benches, antique traffic signals, cobblestone streets, perfectly trimmed lawns, groves of eucalyptus and pine, marble statues, iron grating... and not a single living person or vehicle. Every item found in the “city” has been picked up from historical Buenos Aires and transferred here, right down to the cobblestones. It therefore bears a genuine antique feeling. The fact is, however, it was built only in the 1960s, by a man who was dying of cancer and took it on as a final project for his life. (Incidentally, the man is still alive today, though just barely. His son now rents out the totally private land for films and commercials).

To get to Campanopolis you have to pass through Ciudad Evita, over dirt roads and through some of the poorest outskirts of the capital. As we travelled I studied my lines, as indicated by the “Llamado Diario”, or Daily Call Sheet, which lets each actor know what scenes are scheduled to be filmed for the day ahead. The bus rang with chatting from the excited young actors and technical crew.

When we arrived an hour later, we were quickly ushered to a building nearly the size of an airport hangar. We wandered through its empty interiors that were flooded with light pouring in from the hundreds of windows and climbed the wooden staircase to the second floor.This would be my home base for the coming days, a lofty, mammoth and empty space for preparing the actors and running over lines. The costume crew (two young women) and make-up crew (another couple of women) were already unpacking their equipment. A little further away sat the rifles and pistols, rubber moulds of a baby, cables, artificial blood in jugs, tools and other gadgets of the FX (special effects) team. I was immediately fitted with my clothes, which were too clean to look the part I had to play: pants, shirt, knit vest, and shit-kicking, pointed, steel-tipped cowboy boots that were so big for me I had to stuff cotton into the toes. My eyes were painted black and red eye-liner forced into my lids to give me a drug-addled look. Theatrical grease was smeared into my hair. My hands, fingernails and arms were rubbed with coal black make-up.

I finally met my third brother, Garrett, who had just come in from a small mountain town in Tunisia, just for the filming. He spoke little English, and the English he did speak was basked in a heavy French accent and spotted with Arabic exclamations. How he would work out as my “brother” seemed beyond me; but since he was the producer’s cousin, he would have to work out. I asked Albert about the discrepancy, and he said with his eternally warm smile, “Look, if I could direct Jean Claude Van Damme, who could barely utter a word of English when we did “Cyborg”, I can handle just about anything! Don't worry, it will look great.” As the filming progressed, I started becoming enamoured with the idea of such a strange movie (a western sci-fi action horror flick) studded with largely unknown actors and disparate accents.

To give an idea of the voices to be heard, there is Javier de la Vega, who I hunt down with my brothers in a driven, bounty-hunting frenzy: he hails from Spain and speaks with a British accent. There's Janet Bar, one of the leading bad girls, who was born in the States but lived in Israel and Scotland and whose English blends American and Scottish. My "older brother" Garrett is actually Adnen Helali, or Mohamed - as his friends call him, a tall and very warm Tunisian with a thick French flair. Oliver Kolker, my “younger brother” Frankie, pitched in with his Argentine-New York twang, while Victoria "Clementine" Maurette(the leading lady and my murderer) is an Argentine who speaks perfect American English. And of course there’s myself, with my finely-tuned Texas drawl I added for effect. Most the rest of the actors (except for the American-schooled Argentine Andres Bagg, as an excellent "Mobius" ghost) speak English with a Spanish accent, which seems all right for a film said to be taking place in Mexico in 1895.

To give my clothes a more tarnished look, I followed Javier’s lead and dove into the dirt lying around the Campanopolis grounds. Frankie, that other “brother”, and I crawled and clawed at the earth as the costume department brought over buckets of water drawn from a stagnant pond nearby to turn the earth into mud. After a few good skids on my shoulders and knees, I was set. The producer, Michael Najjar, who had come in from Los Angeles and was hanging out for the shooting, joked that he was actually worried because I looked like I was “almost having too much fun” playing in the dirt. But Garrett’s (Mohamed’s) clothes turned out to be irreparably new: creases still lined his shirt and pants. There was no time. Albert Pyun is famous for working at lightning speed – where some directors take three months for filming, he takes two weeks – and Albert was already finishing up the first scene with Javier. Now Albert wanted to inspect the brothers.

We stood before him like little kids asking mommy if we were dressed okay, and his experienced eye immediately noticed that our belt buckles were too shiny. He also wanted grease and mud smeared onto our neckerchiefs. He wanted us even more dirty. As we worked on that, with the girls from costumes spray-painting our buckles, tearing off shirt pockets and buttons, and rubbing our necks with black make-up on a pumice-like sponge, Albert continued his filming of an unrelated scene. For those of you who never gave it much thought, movies are not made in the order of their scripted scenes; in fact, one single scene may even be filmed in entirely different places.

When we returned to Albert in the midst of his work, he glanced at us and kindly but firmly stated that he could not film us like this and wanted our costumes ready by Friday. Therefore, the rest of the day I had nothing to do but hang around and watch my companions practicing their lines and preparing for their own scenes. I took photos, talked to the producer and learned from the FX man, Gonzalo Pazos, how to sling a shotgun and a pistol. (The shotgun was too heavy for me to raise with my right hand, as I have a serious sprain on my middle finger that I earned from jiu-jitsu practice a month earlier). The hanging around would have been boring if it hadn’t been so damn interesting. At the end of the day they paid me 300 pesos (about sixty percent of my monthly apartment rent) and we all returned on the school bus back to the capital.

The next day of shooting would be Friday the 19th, and Albert promised me it was going to be "an intense day". I would have to catch up for today’s shooting and add in Friday’s work on top of it. Actually, I didn’t mind at all. Meanwhile, friends, be sure to visit the official "Left for Dead" website at http://www.sofiafilmgroup.com/

DAY TWO OF SHOOTING - FRIDAY, JANUARY 19, 2007

“Conner’s” clothes and boots were in a perfect stack and waiting my arrival at Campanopolis. As I changed, Albert Pyun was already calling us to work. The first scene to be filmed today would be “Dead Man’s Walk”.

In the script, my brothers and I are hunting down “Blake” (the Javier guy from Spain with the British accent. Blake has lead us straight into the devil’s jaws - the fearful ghost town of Amnesty – by way of “Dead Man’s Walk”, the only way in or out of that haunted town. The “Dead Man’s Walk” is a broken and rickety wooden bridge with missing planks; half of its trajectory is gone, and it is one of the few parts of Campanopolis that has fallen into decay. The sound team taped wireless microphones to our chests, clipping the transmitters into our pants beneath our shirts. The make-up crew put sun block on our faces beneath our “dirt” so that our complexion would not change over the coming days. Pyun directed his "brothers" to come into the view of the camera, one after the other, by calling out our names. When I come on I pause, look over the edge, look back at my brother Frankie and taunt him with, “The story says hell's at the bottom” before charging onward, Amnesty looming in the background. We spent about two hours on the bridge, in the growing morning heat, shooting the brief scene with close-ups of each other’s faces and with longer shots. The bridge rattled and shook so much that we had to jump over certain planks as we moved across its surface to avoid shaking the camera. We were concerned that we might accidentally step into one of the holes. After the scene, the omnipresent catering service offered us trays of cookies, drinks and fruit.

My feet and ankles began to burn and ache from the awkward fitting and uncomfortable pointed-toe boots. Calluses had formed from running over the cobblestone streets. Also, the leading male character, Mobius (Andres), had a juicy blister forming on his trigger finger from practicing his pistol twirl, so the FX team was obliged to add bandages to his hands that would have to remain throughout the shooting of the entire film.

In my ignorance, I had always imagined that the director sits behind the camera, but now I had learned that he or she actually directs the actors while watching from a monitor situated several meters away from the camera. The camera operator is the one behind the camera. Pyun sat with the director of photography at the monitor, yelling things like “pictures up” (when the guy with the clapper is supposed to announce “scene 4, take 3” and snaps that widely recognized zebra board), and “action”, “cut”, “again”, and the prized “it’s a print!” (which means that Pyun finally liked what he saw on the monitor, resulting in a hearty round of applause).

The next scene to come up was a bit more complicated than the one on the bridge. In this one Frankie and I watch in horror as my brother Garrett (our sweet Mohamed) receives a blow from a butcher’s hook into his abdomen and loses his guts before our eyes. The actual close-up of all the guts had already been filmed a few days ago (along with the rest of the guts scenes throughout the movie) - with the participation of Gonzalo's FX team and without actors: they employed mannequin chests, theatrical blood and cow intestines. Now it was time for the scene to be built up around the guts.

I should mention that in the story line, Garrett has already had his pistol hand blown off a few moments earlier by a shower of bullets (a scene which we would actually film later today) and therefore he has no hand for the present scene. Therefore, first things first: the FX team had to wrap yellow duct tape around that hand, which is the color required for the computer graphics team to be able to make the hand look like a bloody stump.

Next, Garrett would now be fixed up to lose his guts; he would try to hold these in with his other hand for the medium and long camera shots. FX mixed up a concoction of rope, string and rags soaked in a thick, reddish black theatrical blood. Then they taped the length of Mohamed's inner forearm with a shallow bag about the size of that arm. The “guts” were poured into the bag and, as the top of the bag remains open (along the entire length of his forearm), Mohamed had to hold his arm horizontally, with the inner face close to his stomach. When we were all set and in position, FX poured an extra cupful of blood into Mohamed’s mouth. “Reaaaadddyyy….” Pyun yelled, “aaaaannnnnd…. ACTION!” Mohamed slammed his inner forearm into his stomach, copiously splashing the dangling guts all over his forearm, over his shirt and onto the cobblestones. He spewed the blood from his mouth as he toppled in shock towards us, his terrified brothers. I shout, “What the bloody hell!!!”, stumbling backwards, and Garrett falls on top of Blake.

At the shoot-out that builds up to this gory hook mess, it seemed that Mohamed just couldn’t express the sufficient amount of shock and surprise at Mobius' terrifying approach. Mobius (Andres), who throws the hook, is an ominous presence and Albert realized that Mohamed would need a little extra encouragement. In a small break, I noticed Albert was whispering with Andres while we brothers worked on a few speedy rehearsals. When we were prepared for the actual filming, there was still some concern over whether Mohamed would be able to express his terror on cue. Then suddenly, at “ACTION” - and to everybody’s surprise - Andres suddenly jumped onto the street like a bloody vision from hell (though still off camera) and shouted at the top of his lungs, “MOHAMED YOU FILTHY SON OF A BITCH, DIE, DIE DIE!!!!” and unloaded his full stature in a series of “BANG BANG BANG BANG” screams that not only got Mohamed shooting off his left-handed pistol in wide-eyed shock but put both Frankie and I into an equally confused and firing state. I thought something had gone haywire, a horrible error had been committed, and I shot off my pistol wildly. When Albert yelled “CUT AND PRINT!”, everybody knew it had worked. An uproarious applause rang out around us from cast and crew, and Andres apologized to Mohamed for his rude shouting and that he had just been following Pyun’s directives. For the final touch, of course, Andres’ voice would be edited out and the gunshots dubbed in. Our faces registered the rest: Pyun told us that we all looked crazed out of our wits.

The scene doesn’t end there. Frankie and I must fire our guns into this Mobius apparition that just keeps moving closer. This time, Mobius does walk onto camera. I had to put kneepads beneath my pants so I could drop convincingly to the stone street in stupefied fright. Mobius shoots Frankie in the neck, killing him immediately (Oliver takes a flying dive backwards onto a hidden mat). The menace then approaches me face to face. He says he will spare me, but only so that I may deliver a message for him. He then fires a shot into my shoulder, causing me to spiral back in pain. The script says I will have a hallucination that will be digitally edited in later.

Lunchtime arrived and we were all fed at a row of tables half a block long. With no time to get out of clothes and unwind, many of us looked as if we had crept in from the dead.

The next scene we filmed after lunch was with the three brothers scrambling into a church. (In the script, this actually comes just before the Mobius scene I just described above). This is where brother Garrett loses his hand. As we approach the church, I have another line where I tell my brothers something about the place being “hallowed ground.” We are running up to the door in search of Blake, weapons drawn and ready. Oone by one, Albert yells our names, cueing us when to run into the camera frame. We are supposed to have a sudden vision here, so Albert cues us by calling out “VISION!”, and we drop to our knees in blind terror (knee pads again). As there is no vision, of course, no sounds, no nothing, the credibility of our “collective vision” will be dictated by the quality of our acting. I hope you enjoy it! Then Pyun shouts, “GUNFIRE!” and we try defending ourselves by firing off our weapons blindly. As there is still no sound and no real explosions emitting from our guns, we fake that, too. The part where Mohamed gets his hand blown off is filmed separately; it’s a close-up where he lets his pistol fling from his hand. The camera then films us hauling ass and screaming into the church.

Other scenes with other actors were filmed afterwards. Then the three brothers once again had to be filmed running through forest, stopping to catch our bug-eyed wits. We fight over some drugs for a moment (I have another line here, angry that Frankie has been “holding out” on his brothers) and continue into Amnesty. The cast and crew by now had taken fondly to calling us “The Three Stooges”. I imagine that, in fact, we did appear clownish in our constantly freaked out state.

The filming was completed for the day. As I headed for the bathrooms to wash off the make-up, I kept wondering how they would control the light throughout all of this. After all, the action scenes that Albert put together today - which took us about half a dozen hours to create and were filmed at separate times anywhere between sunrise to sunset - only adds up to a few moments of the movie. In my exhausted state I let the thought fade with a series of other questions I had. I rubbed my face with soap and water and cream to get off the “blood and dirt” (not desiring to be cloaked in blood as I boarded the public transport at Plaza San Martin in the city center). I changed my clothes and headed out to the red school bus with the rest of my companions. A happy, accomplished mood was in the air, but there was much less talking than when we had traveled out to Campanopolis in the morning.

DAY THREE OF SHOOTING - SUNDAY, JANUARY 21, 2007

Yesterday was a day off for everybody, but today we're back to work in a new location. Huellas de la Naturaleza (Nature Tracks) is a private natural park that has fallen into disuse. There are plenty of trees and a clearing large enough to set up monitors, sound equipment, tables with drinking water or electrical equipment, and about forty of us. It was hot and the mosquitos were still out at 7am.

The three brothers had a driven day today. With eyes still bleary from the early morning bus ride out here, about an hour from the city, we were filmed one at a time hauling ass through the forest. Albert asked me to put on a hat loosely so that I could lose it in the chase and give the sense of speed as I tear between the trees, shotgun in hand. (The hat actually belonged to Clem, the leading lady, but since I was about to lose it, nobody would notice this detail). We had to repeat the 200-meter dash over a predetermined path four or five times, so the sweat and heavy breathing were real. Then we each repeated the same route at half speed for the close-ups of our faces. This image would probably occupy only about 15 seconds of film and it took about an hour to get down.

Then came the shot where I am about to shoot dead our bounty. The camera is relocated. Acting as if out of breath, I appear from behind a tree and put myself onto camera (my spot marked in the dirt), raising my shotgun. As I have said, there's no sound and no explosion from my weapon, but the script says I graze Blake in the neck. He falls, rises, I re-load my shotgun and take aim... "aaaaaand CUT!" The high-definition video camera is moved to a new position before me, about 25 meters away, and I am now pointing the double-barrel right at the camera. Pyun shouts, "ROLLING" (meaning the camera is now recording) and then, to me, "SHOOT!" I let a fake shot rip and physically add in a small shotgun kick, as instructed by Gonzalo from FX. I have to re-load now, and since I actually carry neither shells nor cartridges (nor having any experience in re-loading) I must turn away from the camera and pretend I am ramming the ammo in. Albert shouts "CUT" and reports that I don't have to turn so far away from the camera to re-load, so we film it again.

As I take aim anew and am ready to pull the trigger, my brother Garrett jumps into the frame from behind the same tree (as if he had just arrived running) and knocks the weapon down from my hands. He grabs my neck (not the last time someone will do this to me) and asks me in his wonderful French accent if I've gone nuts, as no reward would be collected for "bringing back a corpse". "CUT!" Now there's a close-up of the same scene, so Mohamed really has to pull me up to his face. He practices it once or twice with such enthusiasm that I need to remind him not to yank out my hidden microphone. Fortunately, the make-up girl is close at hand, and she dowses my forehead with the water spray gun to give a sweaty look. Garrett then runs off camera and I stay behind to deliver my line: "Well I figure it's better to bring him back dead than not bring him back at all!" Then I race off in the same direction as my brother.

The last scene to be filmed before lunch is of us "Three Stooges" arriving at the gates of Amnesty town. It's a close-up only on us, taken between the bars of the town's supposed front gate, but the "entrance" to the town is actually nothing more than a piece of iron door propped up by some off-camera hands with a branch leaning against it (also propped up by crew hands). The door and branch are unstable, so FX brings in some sort of tripod to hold things in place.

Incidentally, the town of Amnesty that we were "entering" was actually back in that gothic Campanopolis town - there is nothing here in "Huellas de la Naturaleza" but forest: no iron gates, no bridge, no town. (There are, however, some cabins and a dining hall where we would sleep and eat during the coming days of shooting). The magic of cinema has the viewer believe he or she is watching a seamless scene when, in reality, time and geography have largely intervened.

So we arrive at this propped up door and, as Albert reminds us, act as if we had been running for kilometers, out of breath and with spray gun "sweat" beading down our foreheads. We deliver a couple of lines and run past the camera.

Just before lunch I see Pyun glancing around the forest, looking for what may be new ideas on how to take best advantage of the surroundings. Walking to the dining hall (carrying my boots in hand and trekking in my socks to alleviate my aching soles) I ponder the nature of our "rehearsals": all of us practice our scenes only once or, at most, twice, leaving many actors confused on where to stand or how to deliver their lines. And that is how Pyun works. Although some of the actors may fairly not agree, I felt Pyun's spontaneous style maintained a sensation of urgency so important to the film.

At lunch we all ate at a long line of tables, and here I finally got my opportunity to talk and listen to Pyun on a one-to-one basis. He told me how he had left Hawaii at the age of 18 and then headed to Japan, where he had the opportunity to work directly under the great master Akira Kurosawa himself. He also spoke with humble surprise about his receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award, how after all the years of filmmaking people were standing up and appreciating his art. I asked him who his favorite director was, and he replied, "Kubrick". What period? "The sixties," he stated firmly. Then I asked him how he felt being compared to Ed Wood (as I had read on the Internet Movie Data Base), and he smiled, saying, "Well, actually a friend wrote that. You see, some directors have thicker skins than others. I take those words as a comment given in an affectionate light. I mean, someone else might take it as offensive: for example, my friend Tobe Hooper (of "Texas Chainsaw Massacre" fame) would probably take it badly - he's very sensitive."

After lunch it was time for Mohamed to lie in his fresh grave and be readied for blood effects. If you recall, he had lost most of his guts and, miraculously, is still (barely) alive! He had to lie down in his grave and be buried up to the neck. The cast and crew cracked sinister jokes as we all pitched in to push the rubble over his body. Somebody put a script over his face to keep the dirt out. A tube connected to a contraption of compressed gas and theatrical blood was run beneath the shallow dirt and over to his gut. The opening was held in place by some stones. Mohamed announced that he felt refreshingly cool in the earth while the rest of us boiled in the summer heat. He was quickly silenced with a cupful of blood that, once again, would soon be spewed on cue.

When Albert yelled "action", a group of the starring tough girls approached the fresh grave. He then yelled "blood!" (the cue for FX to let loose a gushing of blood from the tube and over the grave), and to everybody's shocked surprise (and barely surpressed laughter) the tube exploded with a powerful geyser. It was a virtual pillar. Despite the unintended exaggeration, the scene continued as planned, with Mohamed spitting and moaning his lines to the women as he pleaded for help. The women respond by shooting him in the head and then continue with a brief dialogue amongst themselves. When Albert finally yelled "CUT", Soledad Arocena, the warmest of souls who had been cast as the blind woman Cota and who had been standing some three meters away, suddenly burst into laughter and announced that she had been splattered all the way over there. They filmed that same shot again, with a better control of the blood, while FX apologized about the gas pressure being too high. Mohamed received great applause for his dying man's performance as he lie there in his grave, and Albert filmed a close-up of the women's faces for their dialogue.

When we dug the Tunisian out I noticed that he was shivvering. He told me that at first it had been refreshingly cool under ground, but soon his body heat had turned the grave into a virtual oven and, now in the open air, he was freezing to death in the same evening summer that had been making the rest of us sweat. He ran off to take a hot shower.

At dinner Mohamed smiled and told me in his so polite manner how everybody had been kicking dirt in his face during the shoot, how the women were unintentionally standing on his legs as they spoke their lines, and that the blood actually tasted like yoghurt. He then confided with pride how he had finally gotten his breathing down to such a minimal wheeze that by the end of the shooting he was barely moving the dirt that covered him, ably giving the impression of a completely motionless corpse. As he beamed, telling me he felt it had been his best work, I paused and silently decided I just had to tell him the truth. I mean, he was heading back to Tunisia and it would not have been fair not to tell him what I knew: his yoguic breath retention was actually being performed during the scene of the girls' close-up dialogue over his grave. I had seen it on the monitor: Mohamed wasn't even on camera! The table exploded into laughter at this, and I hugged my Moslem brother. In his gentelman's charm he had found it equally entertaining.

After the day's work, the sky was filled with stars. Albert headed back into the city with the producer, but the actors who would be needed for tomorrow's shoot stayed to sleep in the cabins provided. We bathed and ate. A group of us hung around on the swingset, talking into the late hours. Actors expressed the joys and difficulties of working with so-and-so actor / crew member. Douglas Sibbald, the clapper (the guy with the zebra board who announces the scenes) confided that he preferred to be called "third assistant" rather than "clapper". He had never left the clapper behind anywhere and carried it with him day and night. Beer and cigarettes were flowed freely and some of us got light-headed. And as a special surprise, Mohamed blew everyone away with a ten-minute wail of a Lebanese mountain song: as he picked up the rhythm we all broke into a cadence of clapping that rang through the night. In the morning we found Douglas had fallen asleep with his clapper in bed.

DAY FOUR OF SHOOTING - MONDAY, JANUARY 22, 2007

One long day today. The three brothers and Blake had to start off early once again. At 7:30am we were already with make-up, costume and weapons in hand. We would be running into the "Cemetery of Lost Souls"... about a dozen times. We wouldn't require the services of the make-up crew to spray our faces with perspiration - we worked up enough sweat just creating the scene itself. It seems we are always either running, screaming, shooting or dying. Ahhh, the life of the bounty hunter.

We start about 200 meters back inside the forest, off camera, and as Albert shouts our names one by one, we go tearing off into the camera frame. We burst into the cemetery, which is a small plot of earth sprinkled with a handful of crooked wooden crosses in the bush, and then gasp for air as we deliver our lines. My line is spoken to my brother Frankie, again trying to scare him (while convincing myself that I am not scared at all): "Cemetery of Lost Souls, Frankie! Like the ghost story says! If the ghost - Mobius Lockhardt the Hellbringer - gets you, you stays here - with him! Feedin' life to his dead soul!"

This once again illustrates the function of the three brothers at the beginning of the movie, as Albert would later tell me: "I don't know if you guys appreciate the importance of your role in the script. You guys are here to introduce the spectator to the world we are about to visit - the cemetery, the town of Amnesty, the church, the bridge that is the only way in or out of the town, etc." After chewing on Albert's words for a while, I wandered away pondering how short-lived our importance was. After all, we spend all our bullets, get smashed in the face with hallucinations, get shot, murdered and buried... and all in less than twelve minutes! How's that for living fast and dying hard!

We also shoot a scene today of me crawling into the cemetery on my hands and knees (call in the knee pads, please!), possessed by the spirit of the evil Mobius ghost. The FX team gets liberal with the blood on my chest (this scene comes just after Mobius shot me back in Campanopolis a few days ago to "deliver a message"). I find my brothers in their graves, pretty bloody. I do my best to act out the scene in shocked weeping, but Albert shouts "CUT" and tells me that here I am entering a trance and must have a vision that overcomes me. Without having had any previous practice or thought on the matter, I was baffled. How was I going to be able to cry over my brothers and at the same time enter into a mind-numbing and shattering trance? Before I could even feel how it should be, Albert was already yelling, "aaaaannnnnd....ACTION!" So it came out how it came out. I hope it looks convincing on film because I think it's going to be a close-up shot.

The blood is a blend of water, a thickening agent that looks like gel, and coloring. I watched Sebastian of the FX team mix up a bucket of it with a 3-speed blender, as if he were preparing a cake in his own kitchen. The blood would be copious today.

I have my vest and shirt ripped where the gunshot had hit me. Make-up darkens the skin beneath. Every time we repeat a scene, the FX ream comes out with their mustard dispenser and squeezes it into the gash wound until it drips all over the place.

The BIG SCENE for me today is my own death. I go running into the camp of men-hating women. Out of my wits, I burst into a private ceremony (quite bizzare, and I don't want to spoil it here) by screaming my head off that Mobius the Phantom is real and alive (this is his message that I was to deliver for him, remember?). I am hallucinating and threatening the boss lady who had paid my brothers and I to go out and capture our bounty, Blake. I tell her that if she wants Blake she can go and get him herself... "He'll be waiting for you", I say, meaning that the terrifying ghost will be waiting for her. She grabs my neck and asks for the name of who, exactly, would be waiting... and as I say the word "Mobius" I spot what I believe to be Mobius himself in the woods. I grab a pistol out of the hand of one of the women in the camp and begin shooting wildly at the figure, shouting for him to stay away from me and that I had delivered his message as he ordered and so, now, "What the hell do you want from me?" And BOOM! That's it. I receive a shotgun blast from the woods, flip backwards and die on the spot.

To shoot this scene we had to film it about ten times, from different angles and using the Steady-cam. The steady-cam is the camera itself hoisted up onto a harness worn by the camera operator (kudos to Daniel de la Vega). The camera is a heavy (and quite expensive) piece of equipment, and Daniel pivoted it around on his hips (with Albert's direction) during my death scene. I later watched it on the monitor and got a real kick out of the movement. It was shot with grace, and I was overjoyed to have died my miserable death in such glorious terms.

Something funny did happen, however, during the shoot. I hate to tell it here because, for me, it takes away from the drama of the scene. Nobody noticed the error until I mentioned it as some of the cast and crew sat around watching the monitor later, and they all replied that it is not discernible - but for me it was a glaring error on my behalf! Here it goes:

As the scene was being prepared, I was back in the woods, waiting for Pyun's "Brad!" that orders me into the scene where I burst into the women's camp. The scene itself was elaborate, with half a dozen extras and the steady-cam weaving around them, so they were taking a lot of time getting it down. I was standing in the woods, bored and practicing my lines, and I called in FX to cover my wound with blood because what I had was drying out. FX Gonzalo came out and told me to cup my hand with fingers tightly closed. He squeezed the mustard dispenser into my curved palm and filled it to the brim with soupy blood. He then told me to hold my hand in that position until they called out "ACTION", when I would smash my palm into my wound as I ran onto the set and create a bloody mess all over my chest and arm.

Time passed. I watched Vicky (the leading lady, Clem) feeding a horse. I faced a tree and delivered my lines to it. I kicked twigs out of my path. I peeked through the trees to see when the actors would be ready. I was getting restless and my hand grew numb from the position it was in. In my own world, humming to myself some insipid tune, I suddenly heard the adrenalin-pumping words "aaaaaannnnd ACTION!" I tore out of the woods, screaming my head off, bursting into camp, threatening the boss lady. As I machine-gunned my lines, I realized that I had run the entire route onto camera with my hand cupped and held out, as if I had been begging for dimes! I had completely forgotten about the blood in my hand! It had been in the same position for so long, as I practiced my lines, that it had cramped and locked itself there! Finally, in the midst of all the action, I remembered to splash the blood onto my chest.

On the monitor I painfully watched in silence and then told the rest about the poor quality of my hand acting. Nobody seemed to have noticed. They rewound the tape, watched it again and assured me that it just looked like I was carrying my blood around. Martin (the "Bear"), the director's assistant, empathized and had to tell me that this was most likely the scene that would be used for the film. Oh, well.

Anyhow, in this scene, when I get shot I fly backwards to the ground. There is no mattress placed here for me because the camera moves about quite a bit and there are too many women that must walk around my body. So I worked up my best martial arts posture, took the shotgun blast like a man, and did a backwards swan dive into the dirt. Everybody said it looked great.

Later in the day there was a brief shot of me crashing through the bush, screaming bloody murder. It was a cut and a print. Later, Albert would send me this shot as a still from the movie and it appears in the collection of photos at their site at www.sofiafilmgroup.com .

I learned about how directors do something called "cheating" a shot. This is when, for example, the characters may be widely scattered around during a shot, and when the camera changes angles they might not appropriately fit into the new frame. Cheating is when the director staggers the people into a position different from the one they had just been standing, thereby allowing them all to fit in the frame. The shift may be huge, but on camera it goes largely unperceptible.

There were also a limited number of weapons to go around today, what with all the extras and scenes where gun-wielding villains appear left and right. Clem (Vicky) and I went back and forth with her pistol, and everybody rotated their weapons.

Pyun has been very fast and unpredictable. He often changes the order of the shooting of scenes for the day, and sometimes the actors are not sure of what his or her next lines will be. The day goes quickly and we sometimes have to wait another day to finally make it to a previously planned scene, even after having been smacked with make-up, rubbed with dirt, taped up with the mike, practiced and prepared. We can't go anywhere because we are paid to be on call for any sudden changes. Nonetheless, I simply marveled at Albert's brilliant, intuitive style. I trusted that he knew what he was doing. He seemed so calm and cool on the outside even when he was blasting like a tornado of creativity on the inside. While some moaned about the experience, I found it exhilarating.

During parts of the day I took advantage of the fact that my character was so dirty I could just lie around anywhere I damn well pleased between scenes: I sprawled out in the leaves, on the dirt, in the mud, wrinkling my clothes, dripping tangerine juice down my beard and staining my pants. It didn't matter. I was a bounty hunter, damn it!

Well, that pretty much wraps up the notes that I took during my four-day stint in an Albert Pyun movie. I hope you enjoyed the ride.

JUNE 4, 2007 - KEEPING IN TOUCH WITH ALBERT

I have been in contact with Albert since the shoot. He has been kind and thorough in keeping me informed of the latest developments. In a personal communication he wrote (and I print all of his e-mails to me here with his express permission):

"There's about 600 effects shots which are being done by digital artists from Bellingham Washington to Cape Town South Africa to Buenos Aires. Global effort. A temp mix is also underway with sound, dialogue and music editors

working up in Santa Barbara, California to create a screening soundtrack. The final soundtrack won't be finished until September." He then added, "It is a masterpiece. It will surprise everyone who worked on it, as I don't think anyone really could imagine what I had in my head. But it's a nervous, stylish and very emotional film. Kind of dazzling in the telling with dynamic performances and a real jangly edge to everything."

Then, in another communication, here's what Albert wrote to me:

"Hi Brad: I enjoyed the experience immensely. Very proud of how you, Oliver and Mohammed did, and you will be too. I know it's kinda hard to envision how it will be put together, but the material we got with you three was really quite remarkable, even if it did take a bit of effort from all of us to get us to where the scenes needed to be. Thanks for your kind patience and generosity in my pressing demands and slightly confusing directing style.

This is the best film of my career. By far. I already know this. And I'm so grateful to you all for giving me this gift at this point in my career. It was kind of overwhelming to watch the film take shape in such an extraordinary way. And that's a credit to you and the cast and crew.

If you see anyone from the cast or crew, please pass along how grateful I am. I was blessed by you all and received a level of work I've never had before. I hope I didn't and don't screw it up and I hope I prove worthy of everyone's faith and talents... I hope it brings you all the same joy and excitement that I had watching everyone's work on set.

Again, and again...my gratitude for giving me a film I never thought I'd ever make.

Best,

Albert"

About a month later, Albert wrote once again - and not without his usual sense of humor - to keep me updated on the progress of post-production:

"The film itself seems to be working very well now. We managed to straighten out the story confusion that dogged our first couple screenings. We've had to make the film more linear so its easier for the audience to meet and get to know each character before moving to the next. Its slows the pace of the film, but it gives the viewer time time settle into a very complex and convoluted storyline. It's worked well enough for us to get two distrib offers from the first two companies we let see the film. They were small distribs and didn't have the funds neccesary to acquire a Brad Krupsaw movie. But I wanted to be sure the film played before moving up the foodchain. We have one DVD screener at the Cannes Festival that a select group of foreign buyers will be allowed to view."

And to conclude this re-print series of e-mails, I am proud to add this final note that marks my crowning achievement in my participation of "Left for Dead":

"A powerful moment is when you receive your vision in

the cemetery as you grieve over Frankie. It's frightening and disturbing. We SEE what you see and your eyes go entirely white for several moments in a horrific fashion...then you weep as you rise and run off screaming, "He's alive!". A real high point to the film. You made brilliant choices in those moments and everyone loves it."

...What could I possibly add to that?

"Left for Dead" is scheduled to come out before the close of 2007. See you at the premier!